On Flashbacks & Backstory: How to Write Them Effectively

Last week I posted a blog on pacing and how as writers, we need to balance things like flashbacks, worldbuilding and more. With worldbuilding, I’d say that I’ve done enough research on the subject to not be curious about it anymore. But flashbacks and backstory? Now that’s something I’ve kind of had to learn how to incorporate in my novel.

I basically have this one incident that happens before the start that basically leads to the events of my story. Like, it’s the reason my main character is where she is, and influences her decisions. And there’s a particular flashback that hits her over and over again.

And that’s where the issue lies, really. As writers, how do we make the right call? How do we include glimpses into our characters’ past—flashbacks and backstory—in a way that truly sings.

This is what today’s blog is all about: on writing flashbacks and backstory.

First Thing’s First: Should You Even Include It?

Let’s get straight to the heart of the problem. Say you’ve got a rich history for your characters that have shaped who they are today. Naturally, the urge to share all of it is strong.

But here’s the thing: readers don’t need to know every part of your character’s backstory. Sometimes, the most important details are the ones left subtly simmering beneath the surface.

One of the most common missteps is the assumption that because a backstory exists, it must be communicated directly to the reader. That’s not true at all.

The real skill lies in discerning what truly illuminates your current narrative and what’s simply extra baggage.

Think of those moments in a story that seem to grind the plot to a halt. Those detours that don’t actually add any real punch by the time you reach the end.

Flashbacks can fall into the same trap if you’re not careful. You end up pulling readers away from your main story to delve into something that might feel disconnected or whose stakes they haven’t yet invested in.

The “Ghost” and Narrative Tension

A truly effective flashback earns its place. Consider F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Gatsby’s relentless pursuit of Daisy, his amassed wealth all geared towards winning her back, forms the central tension. But Fitzgerald doesn’t just tell us Gatsby loves Daisy. He takes us into a flashback to show us a penniless Gatsby believing himself worthless until Daisy. We witness their initial passion, fuelled in part by his disguised social standing in his military uniform.

This flashback reveals what writer John Truby would call Gatsby’s “ghost” – the core psychological and moral flaw driving his actions: the belief that his wealth equates to his worth.

You might think that a defining moment for a character automatically warrants a flashback. But again, it’s all about relevance to the narrative.

While this glimpse into the past certainly explains why Gatsby is the way he is, its power goes beyond mere exposition. It directly fuels the tension surrounding his reckless pursuit of Daisy and deepens the story’s thematic exploration of the failed American Dream.

Flashbacks that truly resonate don’t just offer backstory; they actively contribute to the narrative’s tension and thematic depth.

How to Show (Not Tell) without Including Flashbacks and Backstory

Backstory that simply provide more information about a character, sympathetic or not, can often feel irrelevant and slow the pacing. Honestly, there are often more efficient ways to convey motivation or inspire empathy without forcing the reader to step away from the immediate story.

Showing how past emotional experiences affect a character now can be far more moving. Think of backstory like the tip of an iceberg. The reader only needs to see the parts that directly impact the story, even if you, the author, have a much more extensive understanding of what lies beneath. That’s why those lengthy backstory dumps for every minor character can sometimes feel frustrating.

In my own book, I have a pretty major character with an extremely traumatic past. However, I’ve consciously chosen not to include flashbacks. And yes, they carry immense dramatic and emotional weight and relate to the story’s themes.

This is because depicting the trauma itself wouldn’t necessarily enhance the reader’s understanding of the character or directly build the central tension, which revolves around the ongoing struggle of dealing with trauma years later.

Types of Flashbacks to Consider

So, let’s say that you’ve determined which parts of the past absolutely need to be shown in your book. Now comes the question of how much detail to reveal. Each serves distinct narrative purposes.

Consider how author John Green employs these techniques. The opening of Paper Towns, where Quentin and Margo discover a dead body as children, is a full scene flashback. It’s rich with sensory detail, unfolds over a substantial length, isn’t summarised, and even gets its own chapter.

This signals to the reader that this particular event is deeply significant to the present story in a way that a simple recounting wouldn’t achieve. Furthermore, the added detail lends significant dramatic and emotional weight to the moment.

In contrast, consider a half scene flashback in The Fault in Our Stars, where Hazel briefly recalls spending an afternoon with her father by a river, engaged in simple conversation. This flashback is concise, with minimal quoted dialogue. Half scenes are invaluable for shedding light on less critical moments that still offer insight into a character’s personality or relationships. They don’t risk derailing the pacing either, because they don’t demand a lengthy detour from the front story.

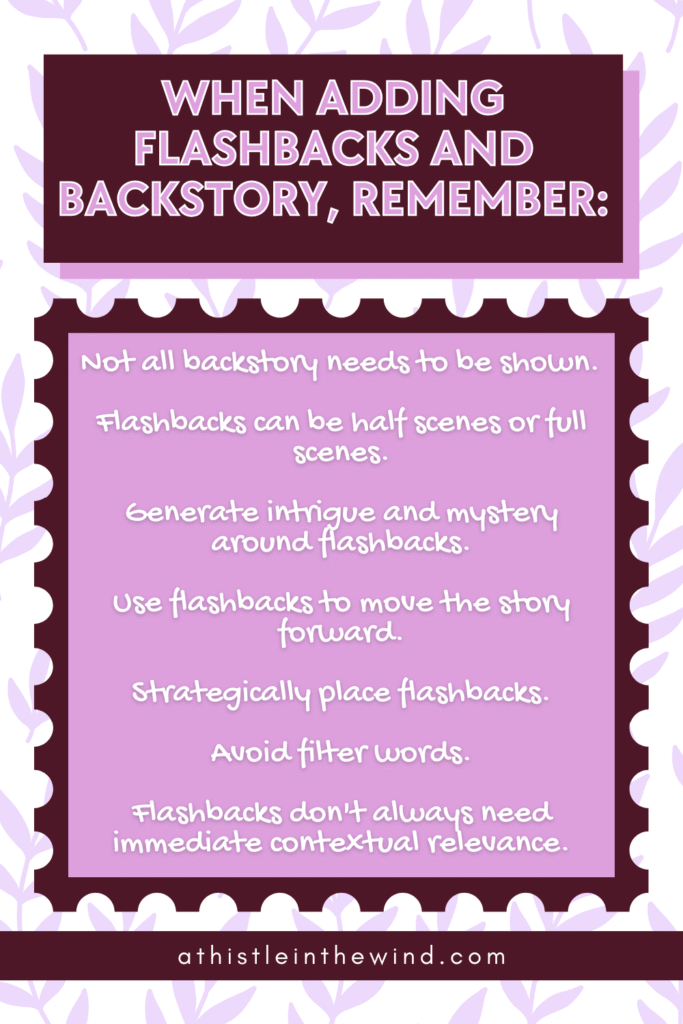

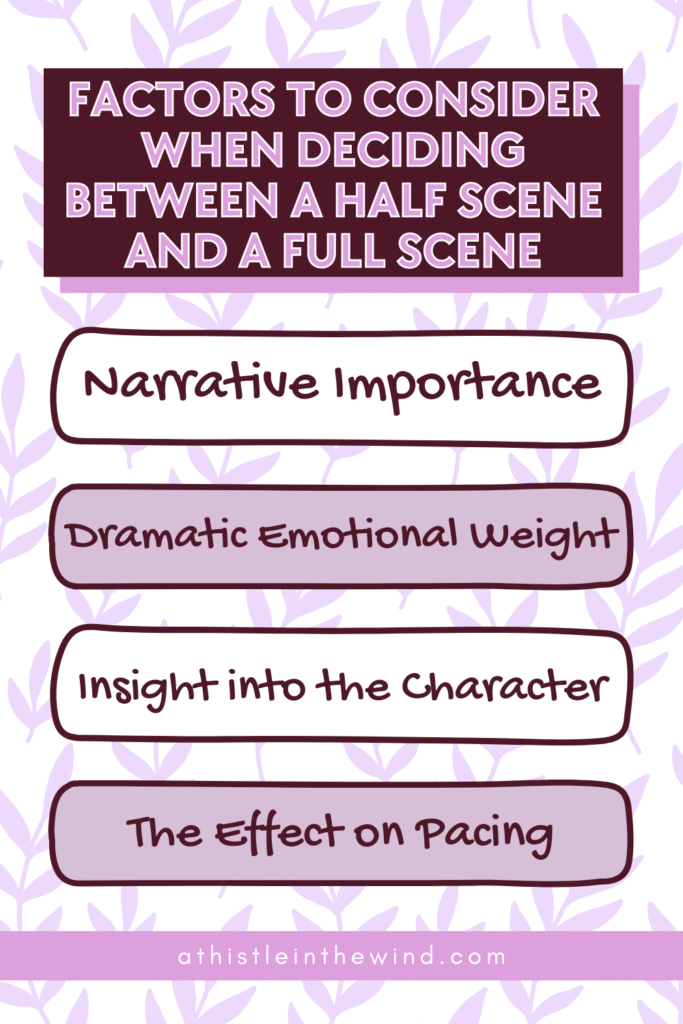

As a writer, you should consider four key factors when deciding between a half scene and a full scene:

- Narrative Importance: How crucial is this past event to understanding the present story?

- Dramatic Emotional Weight: How impactful is this moment emotionally? Does it warrant detailed exploration?

- Insight into Character: How significantly does this flashback reveal crucial aspects of the character’s personality or motivations?

- Pacing: How much disruption to the flow of the main story are you willing to risk?

A Note on Making Flashbacks Work

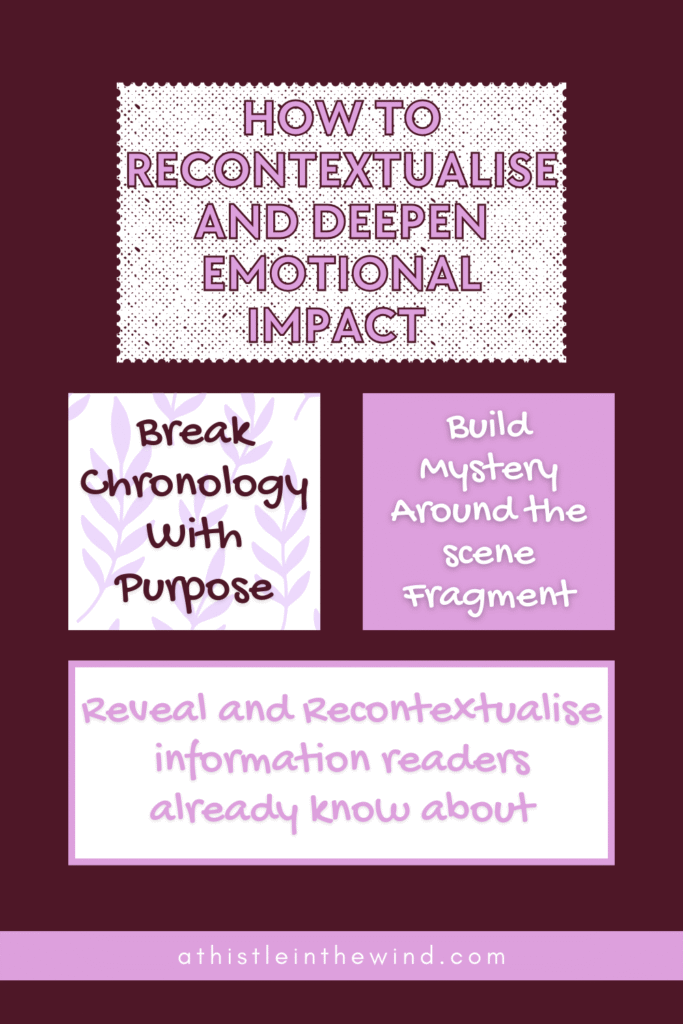

A clever technique to enhance the effectiveness of flashbacks is to generate intrigue and mystery around them before they are fully revealed. Brandon Sanderson aptly described this: flashbacks allow you to build a mystery and then either resolve it or continue it in an intriguing way. Often, it’s less about the information you’re immediately giving the reader and more about the anticipation of what you’re withholding.

Furthermore, when flashbacks work well, they actively move the narrative forward instead of hindering it. They provide the reader with essential context to understand the stakes of the present situation. In the Gatsby example, the flashback deepens our understanding of Gatsby’s motivations. It doesn’t feel like a pause in the pacing at all. Fundamentally, effective flashbacks, while stepping away chronologically, maintain narrative momentum. They give the flashback a purpose beyond just showing the past – perhaps it reveals a foreshadowed secret or introduces a new obstacle.

The Strategic Placement of Scenes

One of the most important things to consider when writing a flashback is not the way you do it is often less critical than the where you place it within your scene structure and the overall narrative.

A common and effective structure involves placing flashbacks so that they comment on or provide deeper context to the front story scene immediately before or after them. Think of Avatar: The Last Airbender.

In the episode focusing on the Southern Air Temple, we see flashbacks to Aang’s relationship with Monk Gyatso, his mentor. This flashback is immediately followed by the devastating discovery of Monk Gyatso’s remains. The flashback not only heightens the episode’s tension surrounding the genocide of the Air Nomads but also adds significant emotional weight to the specific scene that follows.

Flashbacks often illuminate a character’s emotional makeup or explain their thinking, making them a natural fit for exploring the emotional fallout and decision-making processes within reactive scenes. Ultimately, the strategic placement of a flashback within your scene structure and the broader narrative arc is far more crucial than the specific technique used to introduce it.

Use Recontextualisation in Your Writing

Sometimes, a flashback might not directly comment on the scene immediately preceding or following it, yet it can still be incredibly effective. Consider the narrative structure of Ted Chiang’s short story Story of Your Life (adapted into the film Arrival). The narrative is interspersed with seemingly random scenes depicting the main character’s future daughter.

In the short story, these aren’t explicitly presented as flashbacks but rather as the protagonist imagining her daughter’s life. Initially, these nonlinear scenes don’t offer any immediate context or depth to the primary narrative, which focuses on the character’s interaction with aliens.

However, a significant twist towards the end reveals that these seemingly disconnected scenes are actually flash forwards. As the main story progresses, the protagonist develops the ability to perceive future events.

These “flashbacks” are glimpses into her future with her daughter, a future she now knows will be tragically short. This revelation entirely recontextualizes our understanding of these scenes. Their placement throughout the story, though lacking immediate payoff, becomes crucial to the narrative’s emotional weight and thematic exploration.

Had these scenes been revealed only after the twist, their impact would have been far less profound. Because the immediate payoff isn’t there, Chiang employs techniques to maintain reader engagement, such as writing these non-linear scenes predominantly in the second person present tense.

While this initially reads like a mother’s hopeful imagination, subtle oddities, like the sudden imagining of the daughter’s death, create an underlying sense of unease and mystery that keeps the reader intrigued until the final reveal. If you intend to weave seemingly disparate backstory elements throughout your book, this model of building a mystery around them can be highly effective. This technique beautifully illustrates how manipulating story chronology can maximise emotional impact.

On the Weight of Trauma: A Special Case to Think About

It’s impossible to discuss flashbacks without acknowledging their frequent use in depicting traumatic past experiences. Flashbacks are often employed to reveal the origins of trauma, particularly through repressed memories. Full scene flashbacks can be particularly effective here, conveying the importance and intense emotional weight of these moments.

However, it’s crucial to remember that developing reader empathy for a character involves understanding not just the trauma itself but also how it affects them in the present. When depicting a flashback triggered by a present-day event, describing the actual feeling of being grabbed is vital for conveying the traumatic context.

Furthermore, memories, especially traumatic or repressed ones, are rarely accurate or concrete, and they don’t typically return all at once in a neat, chronological narrative. While presenting accurate flashbacks or having a sudden, complete recall of memory isn’t necessarily bad writing, you can also leverage the unreliability of memory for narrative effect.

Remember that people often have fragmented, unclear recollections of the past.