On Worldbuilding Traps: How to Avoid Them

After dropping my marathon of a guide on worldbuilding, I thought that the next best topic to cover would be on worldbuilding traps. Why, you may ask? Well, because you can easily fall into any one of them.

Seriously, it’s something that a lot of writers struggle with. I recently discovered that one of my closest friends was experiencing this problem. She’d gotten so lost into the worldbuilding: the history, the myths—the ethos, even that she’d completely neglected the story.

And we all know how important the plot, among other aspects, of a story is. Of course, you can totally walk yourself out of such a trap. And that’s the point of this blog.

In this blog, I’ll help you identify worldbuilding traps and how to get out of them so you can refocus on your story. But before we move on, let’s get a few things straight.

Hold Up, Wasn’t Worldbuilding a Good Thing?

Yeah, that’s something I was also thinking when I first heard of my friend’s problem. I do extensive worldbuilding too, but I do tend to stop myself before I go down the rabbit hole a bit too much. If you’re new here, here’s the TL;DR: Worldbuilding is the backbone of great fantasy, sci-fi, and dystopian storytelling—it breathes life into fictional realms, making them feel immersive and real.

From the sprawling landscapes of The Lord of the Rings to the brutal political machinations of A Song of Ice and Fire, the most beloved stories of all time thrive on well-crafted worlds. But even masterpieces have their pitfalls. Tolkien’s Middle-earth, for all its depth, sometimes overwhelms with lore, while The Hunger Games occasionally simplifies its dystopian society for narrative efficiency.

These subtle missteps reveal a truth: worldbuilding is a balancing act. Too much detail can drown the story, while too little leaves it feeling hollow. So how do writers avoid these traps? By learning from both the triumphs and stumbles of iconic works. Now, let’s start.

Common Worldbuilding Traps—And How Great Stories Avoid Them

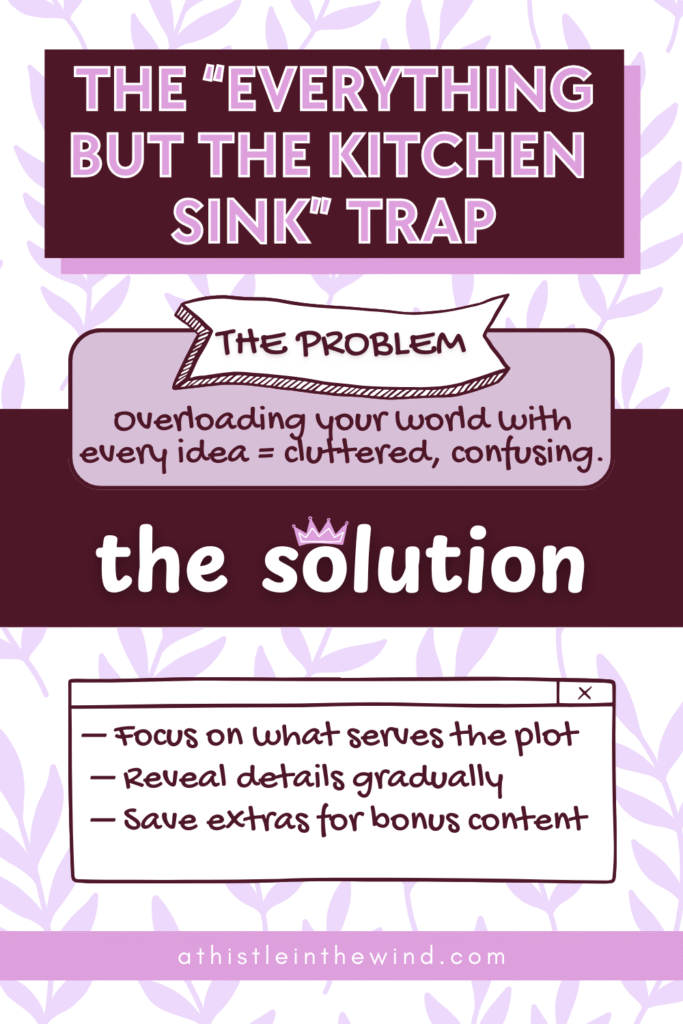

1. The “Everything but the Kitchen Sink” Trap

Overloading a world with too many ideas can make it feel cluttered or inconsistent, leaving readers lost in unnecessary details. Compare The Hobbit—a tightly focused adventure—to The Silmarillion, Tolkien’s sprawling mythos. While both are set in Middle-earth, The Hobbit’s selective worldbuilding serves its story, whereas The Silmarillion’s density can overwhelm casual readers.

How to Avoid:

- Focus on what serves the plot and themes. Not every legend or custom needs full exploration.

- Introduce elements gradually. Avatar: The Last Airbender masterfully unveils its world—Fire Nation history, bending origins, and spirit lore are revealed only when relevant, keeping the story cohesive.

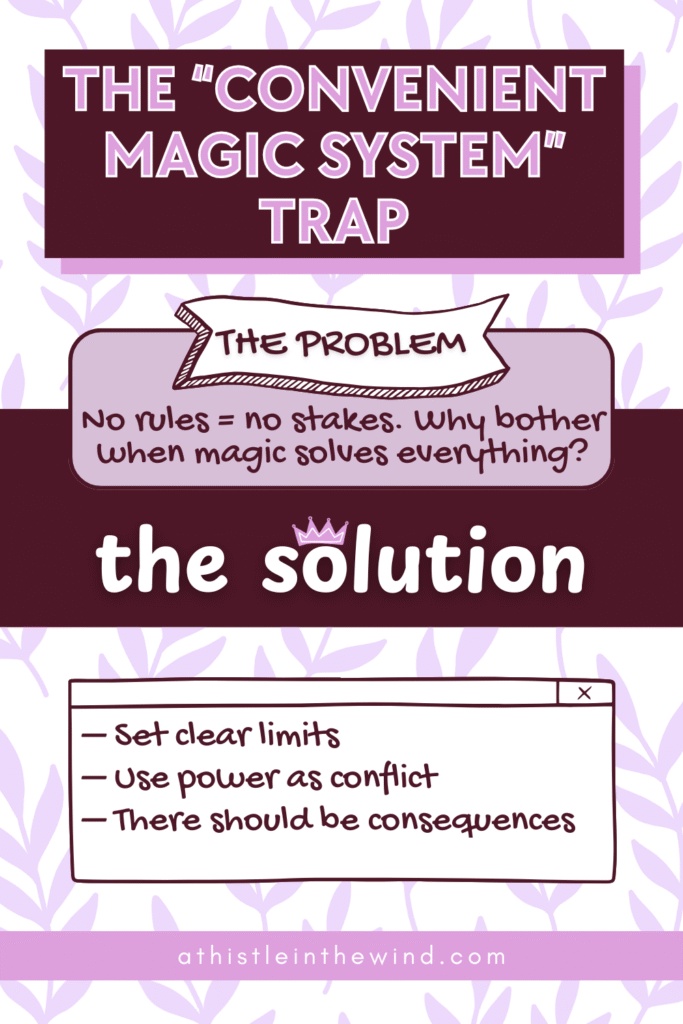

2. The “Convenient Magic System” Trap

Magic or technology that lacks clear rules often becomes a deus ex machina, draining tension from the story. If power has no limits, why doesn’t the hero solve everything instantly? The Lord of the Rings’ Eagles spark endless debate—why not fly the Ring to Mordor? Tolkien’s answer (they’re not a taxi service, and Sauron would intercept them) is logical, but the films risk making their use feel arbitrary. In contrast, Avatar: The Last Airbender enforces strict bending rules: not all people can bend, and only the Avatar can bend all four elements. Simple, yet effective.

Side Note: This might not be true anymore since there’s a new Avatar show coming up with two Avatars and my brain is concerned.

How to Avoid:

- Define hard limits. Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn alloys deplete with use, forcing strategic choices.

- Make magic a source of conflict. In Fullmetal Alchemist, alchemy’s “equivalent exchange” rule drives the plot.

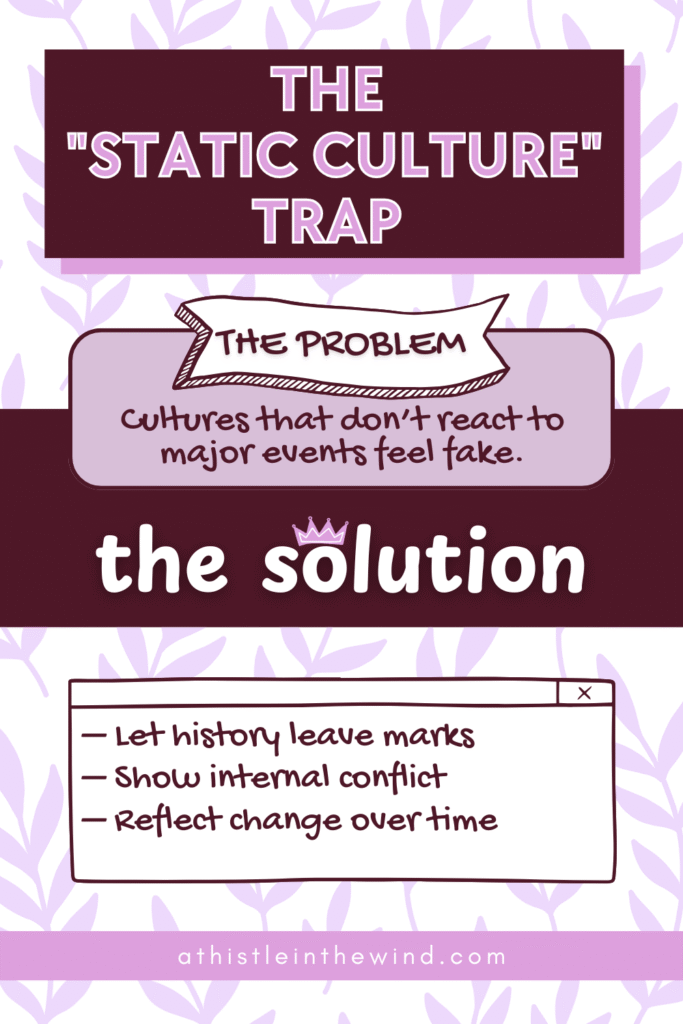

3. The “Static Culture” Trap

Societies that remain unchanged despite world-altering events feel artificial. Real cultures adapt, fracture, or resist under pressure. The Hunger Games’ Capitol maintains its decadence until rebellion forces change—yet real oppressive regimes often escalate control preemptively. Contrast this with A Song of Ice and Fire, where the War of the Five Kings reshapes regional loyalties and traditions.

How to Avoid:

- Let history weigh on the present. Avatar’s Earth Kingdom fractures after the fall of Ba Sing Se, reflecting colonial trauma.

- Show internal dissent. In The Wheel of Time, the Aes Sedai’s political factions make their society feel dynamic.

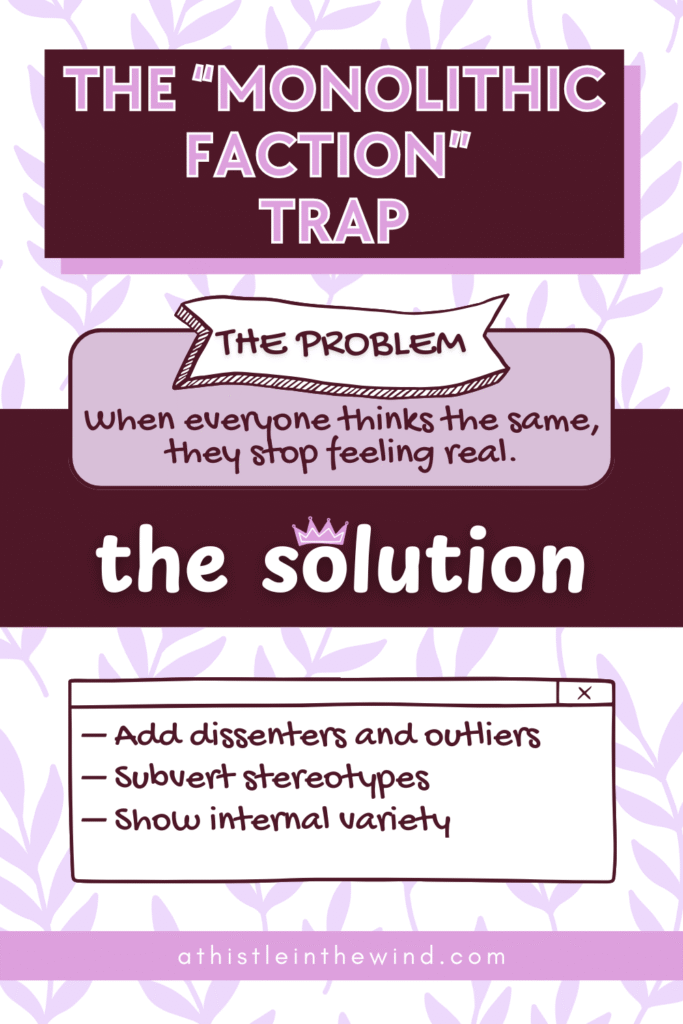

4. The “Monolithic Faction” Trap

When entire cultures, species, or factions act as a single-minded bloc, they become narrative props rather than believable societies. This “planet of hats” trope (where every elf is wise, every dwarf loves gold) strips worlds of nuance and makes conflicts feel artificial.

The Lord of the Rings initially paints orcs as universally vile—effective for mythic tone but lacking depth. Later works like Shadow of Mordor redeem this by giving orcs distinct personalities and rivalries. Conversely, A Song of Ice and Fire thrives on factional complexity: the Lannisters are ruthless but not monolithic (Tyrion’s wit vs. Cersei’s paranoia), and “heroic” groups like the Night’s Watch harbor cowards and traitors.

How to Avoid:

- Introduce dissenters and outliers. Avatar: The Last Airbender shows Fire Nation citizens who resist tyranny (e.g., the deserter in “The Deserter”).

- Subvert tropes. The Witcher deconstructs elf/dwarf stereotypes by tying their struggles to racism and displacement.

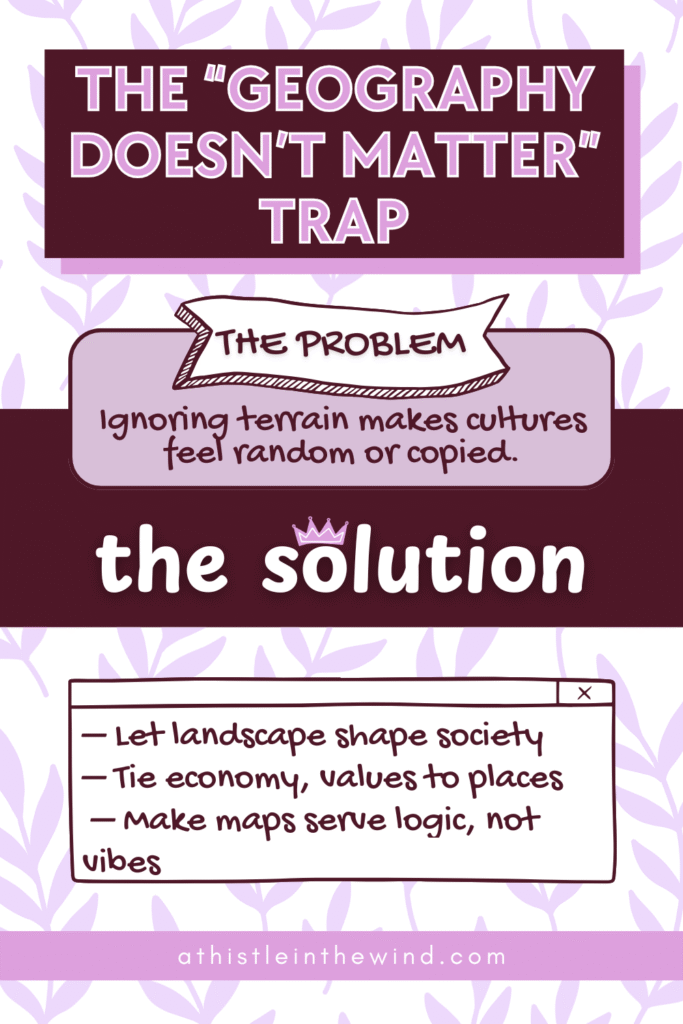

5. The “Geography Doesn’t Matter” Trap

When landscapes are just backdrops, societies feel unmoored from reality. Terrain dictates survival: deserts breed nomads, islands foster traders, and mountains create isolationists. Ignoring this leads to generic “medieval Europe” clones. A Song of Ice and Fire ties culture to geography:

- Dorne’s deserts encourage gender equality (water is scarce; all hands matter) and guerrilla warfare.

- The Iron Islands’ rocky shores create a raider culture (“We Do Not Sow”).

By contrast, The Hunger Games initially glosses over how Districts 1 (luxury) and 12 (coal) physically interact.

How to Avoid:

- Ask: “How does this terrain shape daily life?” Mad Max: Fury Road’s wasteland dictates fuel wars and water worship.

- Let maps serve logic, not aesthetics. In The Wheel of Time, the Aiel Waste’s harshness explains their warrior ethos.

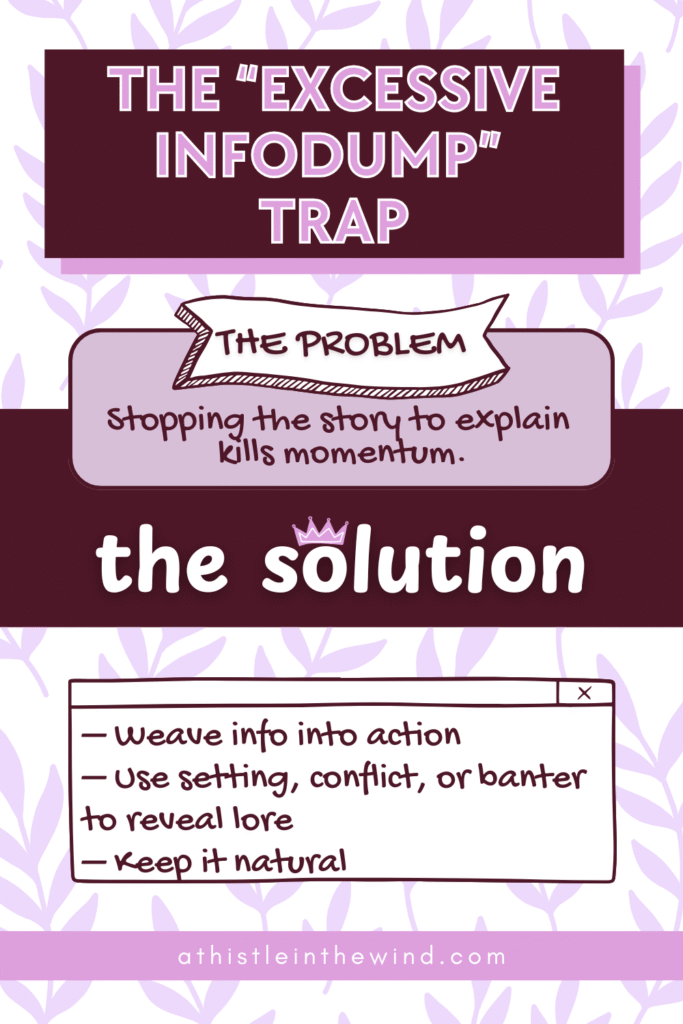

6. The “Excessive Infodump” Trap

Nothing kills pacing faster than halting the story for a history lecture. When writers front-load their world’s lore through walls of text or unnatural dialogue, readers drown in details that should feel alive. Going back to this example. Look at The Silmarillion (can you tell I’m reading this book right now?) —Tolkien’s dense, encyclopedic mythology—to The Hobbit, where lore emerges through songs, riddles, and Gandalf’s offhand remarks. Similarly, Dune risks overwhelming readers with its opening glossary, while The Hunger Games reveals Panem’s oppression through Katniss’s daily struggle to hunt (show, don’t tell).

How to Avoid:

- Bury exposition in action. In A Song of Ice and Fire, Bran’s climbing introduces Winterfell’s layout; in Avatar, Fire Nation propaganda posters show their grip on Earth Kingdom towns.

- Make characters argue about lore. The Lies of Locke Lamora lets thieves debate (and misremember) history, keeping it engaging.

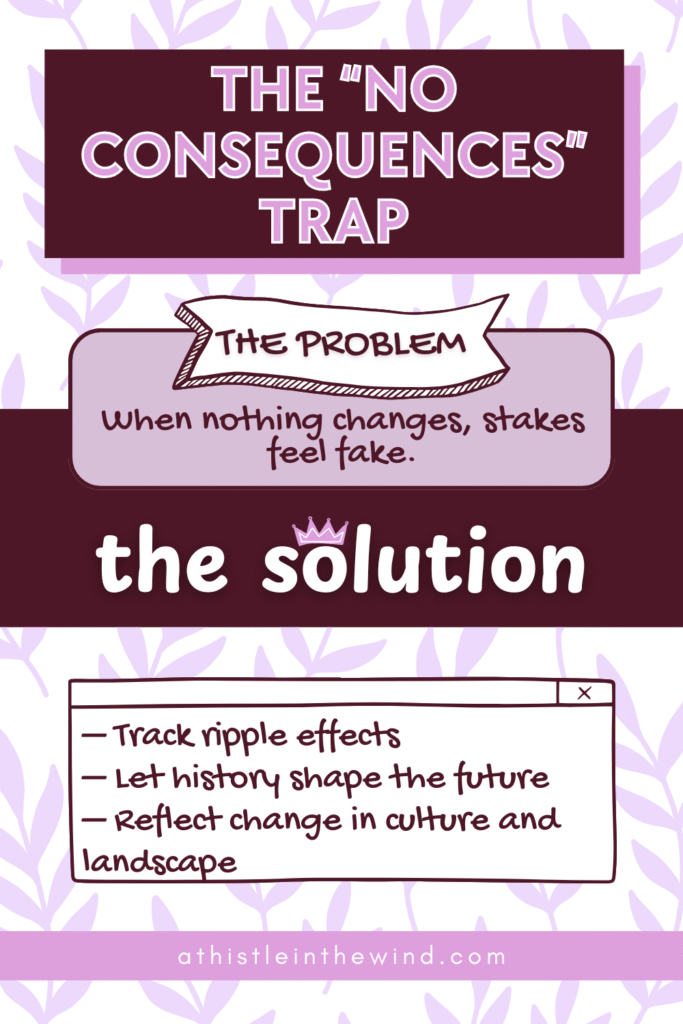

7. The “No Consequences” Trap

A war that leaves no scars, a revolution that changes nothing—these rob stories of weight. Audiences notice when worlds reset after cataclysms. Avatar: The Last Airbender commits to consequences: the Fire Nation’s century-long war leaves colonies, brainwashed soldiers (The Headband), and generational trauma (Zuko Alone). Contrast this with Star Wars: The Force Awakens, where the New Republic’s offscreen destruction undercuts the original trilogy’s victories.

How to Avoid:

- Track ripple effects. The Red Wedding sparks Frey rebellions and Bolton paranoia years later.

- Let geography reflect change. Mistborn’s Final Empire becomes a wasteland of ash-covered skaa slums—then evolves again in Wax and Wayne.

Conclusion: Worldbuilding is…Tricky

Great worldbuilding is alchemy—transforming rules, history, and geography into something that feels lived in, not constructed. The best stories prove that depth alone isn’t enough; what matters is how the world bends under the weight of its own logic.

Yes, even masterworks stumble. But these flaws aren’t failures—they’re reminders that worldbuilding is a process, not a checklist. The goal isn’t perfection, but immersion: making readers forget they’re navigating a fictional realm. A flawed world that reacts (to war, magic, or rebellion) will always feel more real than a pristine one. Now go build something messy, alive, and utterly unforgettable:)