How to Write the Perfect Scene: A Writer’s Guide

I think it’s safe to say that all writers want to write the perfect scene; one that will blow their readers away. A scene that will stick with them long after they’ve turned the final page. Something that will become part of popular culture, something that defines your books or the characters in them.

If you want to write the perfect scene, then you’re in the right place.

Crafting a truly memorable scene isn’t just about throwing some characters into a setting and hoping for the best. It’s a deliberate process that involves careful planning, a deep understanding of your characters, and a keen awareness of how your scene fits into the larger narrative.

Now, every writer has a different process, but I’m confident that with the tips shared in this blog, you’ll have a pretty good idea of what needs to be done.

Four Components That Can Help You Write a Perfect Scene

1. Purpose (Every Great Scene Needs It)

Before you even begin to think about dialogue or descriptions, you need to understand the purpose of your scene. Every scene in your story should have a reason for existing. It’s not enough for a scene to just happen. It needs to actively contribute to your story in some way, whether that’s by advancing the plot, revealing character, or both.

Think about what you want to accomplish with this particular scene, and write that purpose in one sentence. For example, a scene might be designed to show a character losing control, like a hero scaring a heroine with his violent actions.

If you can’t identify a clear purpose for your scene, it might be time to rethink it.

- For more information on deleting or redoing a scene, check out last week’s blog: 4 Signs You Should Delete a Scene: A Guide for Writers

2. A High Moment (Or the Eureka Moment As I Like to Call It)

This is where the tension or emotion of the scene reaches its peak, and it often occurs near the end, or even in the last line of the scene. Think of the high moment as the climax of the scene itself.

For example, a scene might build to a moment where snakes attack, and the high point is the heroine screaming. A great scene should mimic the overall structure of a novel, with a beginning, middle, climax, and end.

3. Conflict (This Can Literally Be Anything)

Conflict is the engine of any good story, and this is especially true for individual scenes. Without conflict, your scene will likely fall flat. Conflict doesn’t have to be explosive action, although it can be. It can be as simple as two characters with opposing viewpoints debating an issue.

Conflict can be external, such as a character battling a physical threat, or internal, such as a character struggling with their own emotions or beliefs. It could even be both at the same time. The key is to make sure the conflict is meaningful and has real stakes. Aim to ramp up the conflict to the highest stakes possible. Don’t have characters argue about coffee, unless it reveals something important about character.

4. Character Development

Every scene should leave your characters changed in some way. Think about how your point-of-view character feels at the start of the scene and how they feel at the end.

This change could be subtle or significant, but it’s essential for the story to advance. Each event in your novel should have an impact on your characters and bring about change. If nothing changes for your characters, why would the reader be interested? For example, a character might start a scene in love, and end it wanting to run away.

Bonus Point: Point of View Matters

Deciding whose perspective you’re going to use in a scene is crucial. The character you choose to tell the story from has a direct impact on how the reader will experience the scene. When choosing your point of view character, ask yourself:

- Who has the most to lose or gain in the scene?

- Who will react the strongest emotionally?

- Who will change the most?

- Whose reaction would most impact the plot?

It’s often helpful to align your point of view character with the scene’s purpose.

How to Keep Your Scene Engaging

Tip #1: Keep It Moving

Don’t get bogged down in unnecessary details. Start your scene in the middle of the action and avoid pages of unimportant narrative. Every word should serve the scene’s purpose.

Don’t include things just because they are there. A great scene opening should hook the reader, and the end should intensify conflict, and underscore character transformation.

Tip #2: Use Sensory Details

Don’t underestimate the power of sensory details. Bring your scenes to life with vivid descriptions that engage the reader’s senses. Your goal is to make the reader feel like they are experiencing the scene themselves, but don’t go overboard. Too much detail is boring, as are details that do not add anything. It’s about choosing the right details to create the right feeling, not just a laundry list of things that are present.

- A house might be described as full of “cubby holes and nooks,” instead of simply “an old, large Victorian house”.

- A book might include a description of a dark book, with a cover of pressed feathers, instead of simply describing “a dark book”.

Balancing Action, Dialogue, and Narrative

The perfect scene strikes the right balance between action, dialogue, and narrative.

- Action is what keeps your story moving and allows readers to visualise what the characters are doing. It’s not enough to have characters staring out of car windows for ten pages – that isn’t real action, and it is likely to bore the reader. Action propels the characters along their journey.

- Dialogue allows you to understand how your characters interact and helps to develop their personalities. It also is an engaging way to deliver information to the reader. However, a scene that only includes dialogue may feel disconnected. There needs to be action and narrative to highlight what is important in the dialogue.

- Narrative provides a window into your character’s internal reflections, emotional responses, and private reactions. It includes descriptions of setting and background information that helps the reader understand how the characters arrived where they are in the present.

However, too much narrative will slow down the pace.

Think of narrative as the glue that holds your entire story together. You need all three elements to create a scene that is engaging, emotionally layered, and moves the story forward. If a scene is too slow, you may need more action or dialogue. If a scene feels rushed, you may need more narrative. If it feels placeless, you probably need more action.

Creating Emotion and Atmosphere

Don’t forget about the atmosphere of your scene. This is the overall feeling that you want to evoke in the reader, and it comes down to your word choice and the details you choose to include. For example:

- A scene set during a massacre might use words like “wailing,” “trilling,” and “screeching” to create a sense of horror and unease. The line about the heat of the bodies could apply to a battle. The sounds could be that of people dying.

- A house might be described using words that feel isolating and alienating, like “thin” and “cigar,” rather than “slender” and “candlestick”.

- A scene that is meant to be hopeful might be set in “brilliant spring sunshine,” with the sun “dancing on the windshield”.

You can use atmosphere to build tension, create contrast, or reveal character. The atmosphere changes depending on the perspective of the character. What might be a creepy atmosphere for one character might feel like home for another.

- For more information on how to write emotions, check out this blog: On Writing Emotions: A Writer’s Guide to Mastering Feelings in Fiction.

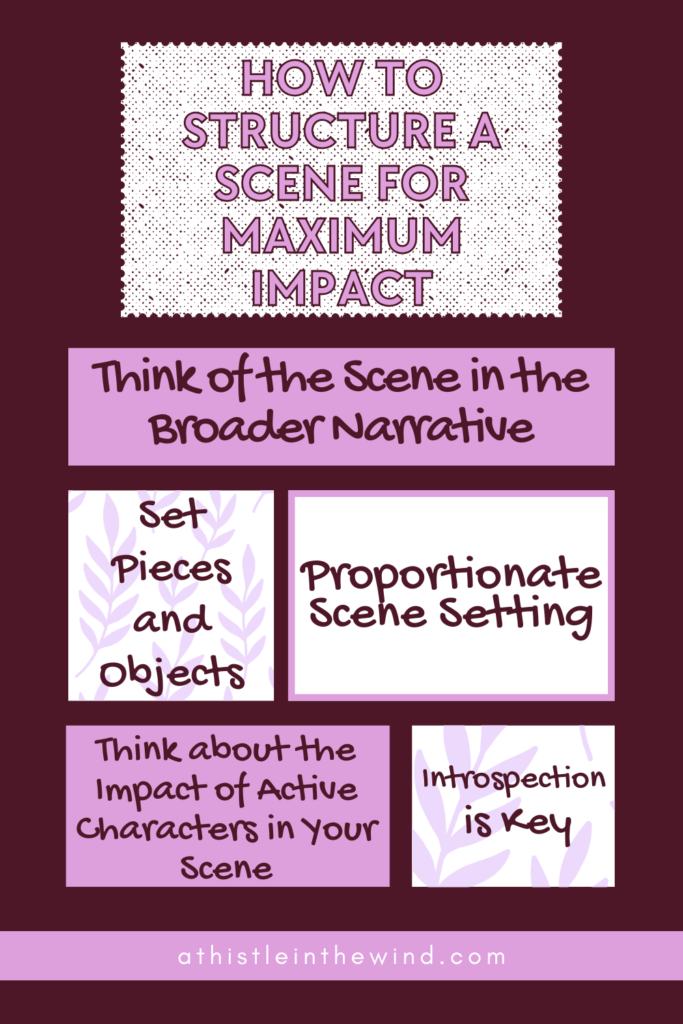

How to Structure A Scene for Maximum Impact

Think of your scenes as questions and answers. You can set a question up in the scene setting, and then answer it in the scene itself. For example, a scene might set up the question “does the violin have a name?” and then answer that question by giving it a name.

The question can also be symbolic. Don’t always use questions and answers literally; they can be subtle. You can use the environment to pose a question, like “What’s in the lighthouse?” and then show that this question is relevant to the overall plot.

1. Set Pieces and Objects

Important set pieces and objects can become relevant later in the scene. For example, the rafters in a wedding scene might become relevant when a massacre breaks out. A chandelier in a play might become relevant when it falls. Make sure to establish these key objects so that the reader doesn’t feel like a wizard conjured them up for no reason.

A crack in the wall of a bank vault is an important set piece if the character is later going to use that to escape. Think of these set pieces as Chekhov’s gun – if you mention it, it needs to become relevant later.

2. Think of the Scene in the Broader Narrative

Don’t forget to consider the place of your scene within the broader narrative. Some elements in a scene may not be hugely relevant to that particular scene, but they will become important later on.

For example, an image of a star might not be critical to the scene it appears in, but it can be used to create a parallel between two characters. Don’t just think about physical objects. Language that you introduce early on can become more relevant and meaningful later in the story, even if not in the current scene.

3. Introspection is Key

Scene setting isn’t just about time and place. Introspection is often more important. The environment is almost always filtered through a particular character’s lens. This is often closer to what the actual story is about. Introspection is what gets the reader grounded in the scene.

4. Active Characters

Start your scene with an active character. Have your characters interact with their environment. This sets the scene at a pace, and establishes the setting. It also prevents the scene from feeling static and allows your character to discover something, be interrupted, or pursue something. An active scene doesn’t always have to be physical; a character can be psychologically active, too. Internalization moves the story forward.

5. Proportionate Scene Setting

Some scenes are short, and that is okay. They don’t need a lot of scene setting. Avoid the temptation to describe every single detail of a setting if it is not important. Make sure that you are putting in enough effort for each scene, according to how important it is. Remember, your readers have imaginations, and you should invite them to use them.

Scene Construction Techniques

I think the best way to ensure that each scene you create is great, is to structure your scenes as either a “Scene” or a “Sequel”.

A “Scene” will have three parts:

- Goal: What your point of view character wants at the start of the scene. This must be specific, and makes your character proactive.

- Conflict: The obstacles your character faces when trying to reach their goal. The reader will be bored if there is no conflict.

- Disaster: The character fails to reach their goal. Winning is boring, and this will make the reader turn the page to find out what happens next.

Similarly, a “Sequel” will also have three parts:

- Reaction: The emotional follow-through to the disaster in the previous scene. Show your character hurting, and allow the reader to feel their pain.

- Dilemma: The character is in a situation with no good options. The reader should worry about what is going to happen next.

- Decision: The character makes a choice from the options available. This allows the character to become proactive again. It must be a good decision that the reader can respect.

A scene leads to a sequel, which then leads to another scene, and so on. It will keep the reader engaged, as your character moves through these steps. Also, note that this is a very general rule. Your sequel doesn’t necessarily have to follow your scene immediately. Depending on your story, and how it’s set up, you can include it in another chapter.

Motivation-Reaction Units (MRUs)

While I was researching how to write better scenes, I came across something that Dwight Swain calls motivation-reaction units.

Motivation-Reaction Units, or MRUs, are a way to structure the small-scale elements of your scenes. It involves alternating between what your POV character sees (Motivation), and what he does (Reaction). The Motivation is objective and external, and the reaction is internal and subjective.

- Motivation: Present the scene as a video camera might show it, with no indication of the point of view of the character.

- Reaction: Show the internal experience of your character, from the inside. Present reactions in order, from fastest to slowest:

- Feeling: The first emotion of the character, because this happens almost instantly.

- Reflex: The instinctive action resulting from the feeling.

- Rational Action and Speech: The rational response to the situation.

You can leave out one or two of these elements, but you must keep the elements you include in the correct order. After the reaction, comes another motivation. Don’t write one MRU, and be done. Write many. If you run out of motivations and reactions, your scene or sequel is over. Every part of your scene or sequel that is not an MRU must be removed.

You can learn more about MRUs in this blog post.

The Secret to The Perfect Scene

Writing the perfect scene is a skill that takes time and practice to master. Remember that it isn’t about being perfect all the time, but about getting a little bit better with each scene you write.

Personally, when I’m writing, I don’t really think about structure and the theory behind the perfect scene. As I’ve said previously. Writing is purely subjective. What I do, however, is after writing a scene (or ten), I tend to go back to these elements and check if my scenes are any good.

Seriously, these “components” are just a guideline. At the end of the day, it completely depends on you—the writer. You can edit your scene when you’re done, choosing which components should go where, and then you’re finished. You’ve written the perfect scene!